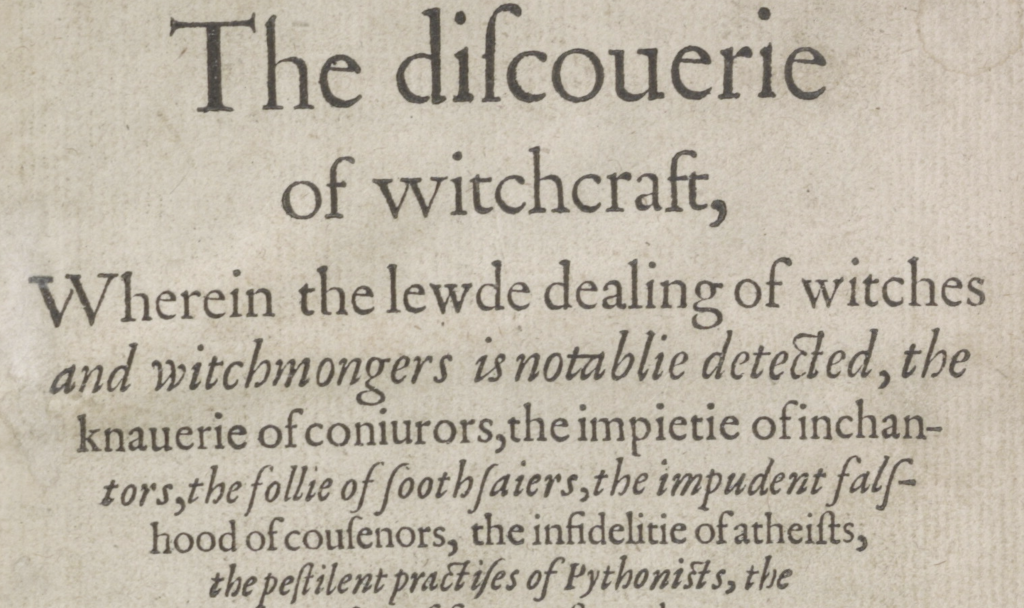

And so it begins…the title page of Reginald Scot’s 1584 edition of “The Discoverie of

Witchcraft.” Rare Book & Special Collections Division.This article was

co-researched and co-written by digital library specialist Elizabeth Gettins,

who also had the brilliant idea for the piece.

You’re forgiven if you think we’re talking about H.P. Lovecraft’s fictional book of magic, “Necronomicon,” the basis for the plot device in “The Evil Dead” films, or something Harry Potter might have found in the Dark Arts class at Hogwarts.

But, as the darkness of Halloween descends, we’re not kidding. A first edition of “The Discouerie of Witchcraft,” Reginald Scot’s 1584 shocker that outraged King James I, survives at your favorite national library in the Rare Book and Special Collections Reading Room. (The Library has a copy of the original edition, as well as a 1651 edition.)

It is believed to be the first book published on witchcraft in English and extremely influential on the practice of stage magic. Shakespeare likely researched it for the witches scene in “Macbeth.” It was consulted and plagiarized by stage magicians for hundreds of years. Today, you can peruse its dark secrets online. How could your wicked little fingers resist? Scot promises to reveal “lewde dealings of witches and witchmongers”! The “pestilent practices of Pythonists”! The “vertue and power of natural magike”!

Also, juggling.

It is one of the foundational examples of grimoire, a textbook on magic, groundbreaking

for its time and nearly encyclopedic in its information. Scot’s research included consulting dozens of previous thinkers on various topics such as occult, science and magic, including Agrippa von Nettesheim’s “De Occulta Philosophia,” in 1531 and John Dee’s “Monas Hieroglyphica” in 1564. The result is a most impressive compendium.

The heavens, as used in witchcraft. “The Discoverie of Witchcraft,”

P. 283. Rare Book & Special Collections.

P. 283. Rare Book & Special Collections.

Born in 1538 in Kent under the rule of Henry VIII, Scot was landed gentry. He was

educated and a member of Parliament. He admired, and may have joined, the Family of Love, a small sect comprised of elites who dismissed major Christian religions in favor of arriving at spiritual enlightenment through love for all. By publishing “Witchcraft,” he meant to expose it as superstition, hoping to better England by forwarding knowledge. Since most people who were accused – and often hanged – for it were impoverished women on the margins of society, he hoped to garner social empathy for them and other scapegoats.

He also hoped to dispel the common belief in magic tricks performed on stage before gasping audiences. To do this, he researched and explained how magicians carried out

their illusions. Beheadings? See the diagrams!

Detail

from “To cut off ones head, and to laie it in a a platter, which the

jugglers call the decollation of John Baptist.” P. 282, “The Discoverie

of Witchcraft,” Rare Book & Special Collections Division.

Detail on how to use a false bodkin. P. 280, “The Discoverie of Witchcraft.”

Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The book was blasted by the religious faithful, according to “The Reception of Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft: Witchcraft, Magic and Radical Religion,” a study by S.F. Davies in the Journal of the History of Ideas, published in 2013. The King of Scotland, James VI, was outraged. Like many of his subjects, he was convinced that witches worked in concert with the devil. He thought a coven of witches was trying to kill him. He published “Daemonologie” in 1597, in part to refute Scot’s work. He also became King James I of England in 1603. There’s a legend that he ordered all copies of Scot’s book burned, but the historical record is silent on the subject. Still, it’s clear James I loathed the book. There was growing concern at the time that women’s use of so-called magic was counter to the aims of the state and church. Thus, James sought to instill fear in female communities and spoke out directly against witches and their perceived occultisms.

“Almost every English author who subsequently wrote on the subject of witchcraft mentioned Scot disparagingly,” Davies writes of the period. Scot died in 1599; the book was not republished during his lifetime. There was an abridged Dutch translation published in 1609, Davies notes, but was not republished in England until 1651, nearly three quarters of a century after its initial publication.

Still, the book survived, “mined as a source on witchcraft and folklore,” and his material on practical magic and sleight of hand “found a large audience,” Davies writes. For Scot’s original aims, that wasn’t good. Rather than debunking stage magic for the masses as he’d hoped, “Discoverie” became a handbook for magicians in Europe and America, well into the 17th and 18th centuries. Famous works such as “Hocus Pocus ” and the “The Juggler’s Oracle“ drew heavily on “Witchcraft,” thus spreading the very mysteries that Scot had hoped to quell. Davies: “[I]t travelled in directions Scot himself may never have imagined.”

Today, 435 years after it was published, the book sits on the shelf, silent, patient, having done the work its author did not want it to do. It’s almost as if…the thing had a hex on it.

via https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2019/10/the-cursed-original-book-of-witchcraft/

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen