Every weirdo in the world is on my wavelength.

Here we are in the high, roiling heat of midsummer and depending on

where you live in these United States, you may be soaking up a sea

breeze or watching the flat midwest horizon shimmer or stewing in a

crowded city subway car. Wherever you are, though, and whatever you’re

doing, there is one thing I think we can all agree on: nothing says Fun

in the Sun like the work of legendarily reclusive wordsmith Thomas

Ruggles Pynchon Jr (yes, his middle name really is Ruggles). Right?Pynchon’s intriguingly dense and zany books, coupled with his ability to maintain his winking hermit persona (unlike, say, the more po-faced, humorless variety practiced by J.D. Salinger) deep into the all-seeing Information Age, has imbued him with a cult status almost without parallel among living authors. In fact, I’d wager that if you lock the doors on any medium to large-sized MFA class or gathering of Aspiring Literary Writers of America, and force everyone to unveil their tattoos, you’ll find at least one Trystero symbol from The Crying of Lot 49 per group.

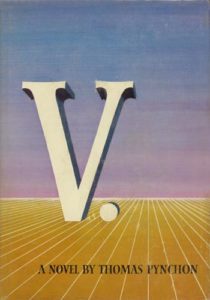

V. (1963)

Life’s single lesson: that there is more accident to it than a man can ever admit to in a lifetime and stay sane.

“For the author, the form of the picaresque is convenient: he can

string together the short stories he has at hand (publishers are

reluctant to publish short-story collections, which would suggest the

genre is perhaps a type of compensation). Moreover—the well-made, the

realistic not being his concern—the author can afford to take chances,

to be excessive, even prolix, knowing that in a work of great length

stretches of doubtful value can be excused. The author can tell his

favorite jokes, throw in a song, indulge in a fantasy or so, include his

own verse, display an intimate knowledge of such disparate subjects as

physics, astronomy, art, jazz, how a nose-job is done, the wildlife in

the New York sewage system. These indeed are some of the topics which

constitute a recent and remarkable example of the genre: a brilliant and

turbulent first novel published this month by a young Cornell graduate,

Thomas Pynchon. He calls his book V.…

“The identity of V., what her many guises are meant to suggest, will cause much speculation. What will be remembered, whether or not V. remains elusive, is Pynchon’s remarkable ability—which includes a vigorous and imaginative style, a robust humor, a tremendous reservoir of information (one suspects that he could churn out a passable almanac in a fortnight’s time) and, above all, a sense of how to use and balance these talents. True, in a plan as complicated and varied as a Hieronymus Bosch triptych, sections turn up which are dull—the author backing and filling, shuffling the pieces of his enormous puzzle to no effect—but these stretches are far fewer than one might expect. Pynchon is in his early twenties; he writes in Mexico City—a recluse. It is hard to find out anything more about him. At least there is at hand a testament— this first novel V.—which suggests that no matter what his circumstances, or where he’s doing it, there is at work a young writer of staggering promise.”

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen