Poor F. Scott Fitzgerald. The highs were so high, but the lows, ultimately, proved too much for him to bear. At the peak of their powers in the early-to-mid-1920s, the young and vibrant Fitzgerald and Zelda lived an opulent celebrity lifestyle funded by the success of early novels This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Beautiful and the Damned (1922), as well as the then quite lucrative side gig of penning short stories for popular magazines. Fitzgerald’s writing, and the couple’s flamboyant (and volatile) conjoined public persona, made them the toast New York high society and garnered them a place among the fashionable expatriate literary set of Paris and the French Rivera.

By the late 1920s, however, things had begun to fall apart. The Great Gatsby (1925) didn’t receive the critical praise that Fitzgerald so desperately hoped for, or the sales required to fund their lavish lifestyle and increasing medical expenses (Fitzgerald’s alcoholism and Zelda’s decent into debilitating mental illness left the pair in a near-constant state of financial panic). For the Fitzgeralds, the 1930s were characterized by creative frustration, crippling self-doubt, mercenary Hollywood hack work, institutionalization, infidelity, acrimonious splits followed by short-lived reconciliations, and, eventually, total estrangement. Fitzgerald died suddenly of a heart attack in 1940, while Zelda followed eight years later when a fire broke out in Highland Sanatorium, where she was locked into a room, awaiting electroshock therapy.

Perhaps the quintessential chronicler of the Jazz Age whose opus is considered by many to be the greatest of the Great American Novels, Fitzgerald’s work shines brighter now than ever, selling hundreds of thousands of copies every year while Zelda, whose own creative endeavors were overshadowed (and, many would argue, frustrated) by those of her husband, has, at least, had her image rehabilitated by in recent decades through reengagements with her writing and life story by Nancy Milford, Therese Ann Fowler, and others.

Below, you’ll find the first newspaper and magazine reviews of all five of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels, from This Side of Paradise to the posthumously published The Last Tycoon.

*

This Side of Paradise (1920)

I don’t want to repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again.

The philosophy of Amory, which finds expression in ponderous observations, lightened occasionally by verse that one thinks could have been evolved only in the cloistered atmosphere of his age-old alma mater, is that of any other youth in his teens in whom intellectual ambition is ever seeking an outlet. Amory’s love affairs, too, are racy of the soil, while the girls, whose ideas of the modern development of their sex seem to embrace a rather frequent use of the word ‘Damn,’ and of being kissed by young men whom they have no thought of marrying, quite obviously belong to Amory’s world. Through it all there is the spirit of innocence in so far as actual wrongdoing is implied, and one cannot but feel that the sexes are well matched according to the author’s presentment.

“Amory Blaine has a well-to-do father and a mother who lives the somewhat idle, luxurious life of a matron who has never known the pinch of even economy, much less of poverty, and the boy is the creature of his environment. One knows always that he will be safe at the end. So he is, for he does his bit in the war, finds afterwards that his money has all gone and goes to work writing advertisements for an agency. Also, he has his supreme love affair, with Rosalind Connage, which is broken off because the nervous temperaments of both would not permit happiness. At least, so the girl thinks. So Amory goes on the biggest spree noted in the book-a spree which is colorfully described as taking in everything in the alcoholic line from the Knickerbocker ‘Old King Cole’ bar to an out-of-the-way drinking den where Amory is ‘beaten up’ artistically and thoroughly. The whole story is disconnected, more or less, but loses none of its charm on that account. It could have been written only by an artist who knows how to balance his values, plus a delightful literary style.”

*

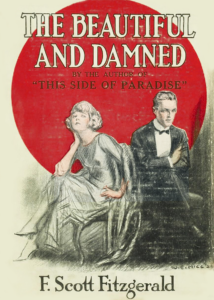

The Beautiful and Damned (1922)

I shall go on shining as a brilliantly meaningless figure in a meaningless world.

…

“So far as its style is concerned, much of the novel is well written, and Anthony’s gradual loss of his mental curiosity, his gradual degeneration into ‘a bleak and sordid wreck’ is convincingly depicted, though to the reader he never seems one-third as intelligent as the author apparently thinks him. The long conversations between Anthony and his two friends, Maury Noble and Dick Caramel, are often merely tedious and pretentious, in spite of the fact that now and then one of them does make a remark which is fairly clever. The general atmosphere of the book is an atmosphere of futility, waste and the avoidance of effort, into which the fumes of whisky penetrate more and more, until at last it fairly reeks with them. The novel is full of that kind of pseudo-realism which results from shutting one’s eyes to all that is good in human nature, and looking only upon that which is small and mean—a view quite as false as its extreme opposite, which, reversing the process, results in what we have learned to classify as ‘glad’ books. It is to be hoped that Mr. Fitzgerald, who possesses a genuine, undeniable talent, will some day acquire a less one-sided understanding.”

–Louise Maunsell Field, The New York Times, March 5, 1922 .... [mehr] https://bookmarks.reviews/the-first-reviews-of-every-f-scott-fitzgerald-novel/

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen