When Adams conceived of the work, he was still smarting over Andrew Jackson’s 1828 victory. To Adams and his supporters, the unscrupulous Jackson heralded a dangerously chaotic set of norms in American politics. The latter’s ostensible disrespect for legal precedent, his cult of personality, and lack of political and moral vision (as well as his penchant for lethal dueling) could not have run further afoul of the high-minded anti-factionalism to which Adams laid rhetorical claim in his political career. Jackson, meanwhile, wielding unprecedented amounts of campaign cash, had driven his supporters into a frenzy over the patrician Adams’ record, charging him, among other anti-American heresies, with monarchism, European-style decadence, Masonry (false, and pointedly ignoring the fact that Jackson actually was a mason), federal overreach, and perhaps most fearfully, the specter of abolitionism. Although the ex-president had presided over a peaceful, economically stable, and bureaucratically well-managed four-year term, he had accomplished little of substance, and was walloped by the ex-general by an electoral-vote margin of 178-83. Resigned, a defeated Adams spent the final weeks of his presidency tending quietly to vegetables, fruit trees, and herbs in the White House garden.

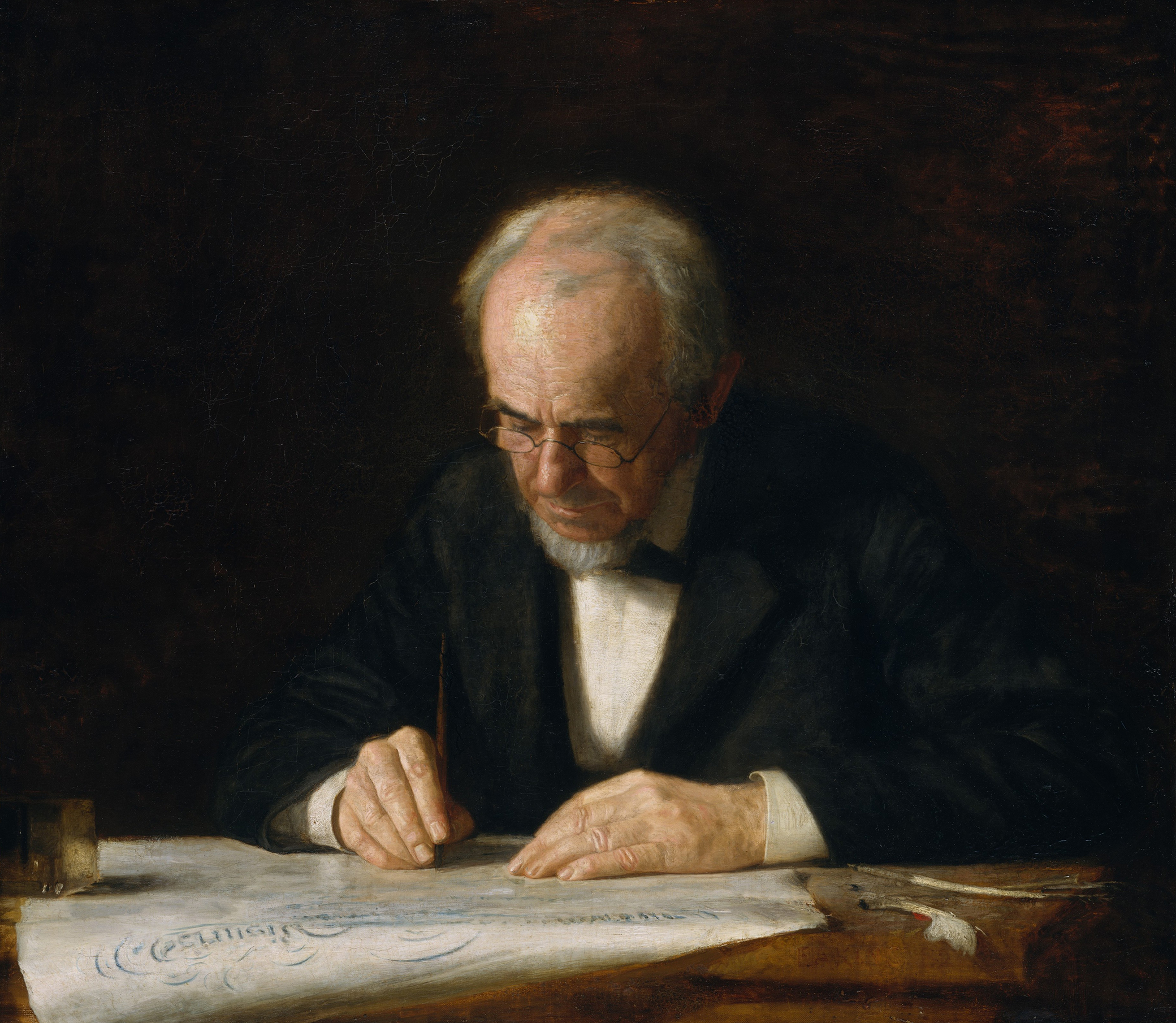

Adams now turned to poetry, a source of both amusement and sustenance throughout his life and career. His earlier efforts had run the formal gamut, including a youthful Romantic paean to the cliffs of Dover, a love poem to an idealized, indifferent beloved, satirical sketches of the young society ladies of Massachusetts, a playful account of his maid’s unexpected pregnancy (based on a true story, and concluding happily with a baptism and marriage), even an ode to a particularly revealing dress, which his wife Louisa characterized as “the sauciest lines I ever perused.” But despite his occasional (and comparatively modest) forays into prurience, Adams was most at home in a didactic, religious mode. The better part of his poetic output consists of short, lyrical expressions of spiritual devotion—the pious hymnals that would eventually be collected in the posthumous Poems of Religion and Society, the anthology upon which Adams’ modest nineteenth-century reputation would rest. Adams’ best-known poem at that time was 1841’s “The Wants of Man,” a measured consideration of heavenly and earthly pleasures. (“My last great Want—absorbing all— / Is, when beneath the sod, / And summoned to my final call, / The Mercy of my God.”) It would later appear in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1874 edited anthology Parnassus alongside Wordsworth, Milton, and Tennyson, in a particularly botched attempt at forecasting the canon. ... [mehr] https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/yawns-innumerable

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen