Jerome David Salinger, the man the New York Times

once described as having “elevated privacy to an art form,” passed away

nine years ago this week. At the time of his death, despite not having

published a book in almost fifty years, Salinger was still a (literary)

household name. There were a number of bizarre but undeniably

fascinating reasons for this, chief among them his almost mythic

sustained reclusiveness and the enduring popularity of his now-canonical

1951 debut, The Catcher in the Rye (which has now sold

somewhere in the region of 70 million copies worldwide). There was also

his early romance with Eugene O’Neill’s daughter, Oona (who ghosted him for Charlie Chaplin); the intense legal dispute with biographer Ian Hamilton, which culminated in Salinger suing Random House;

a relationship with eighteen-year-old journalist Joyce Maynard when he

was fifty-three; two revealing memoirs published within a year of each

other at the close of the 90s—one by Maynard and another by Salinger’s

daughter, Margaret; and the ongoing speculation that his aberrant

behavior stemmed from his WWII service and the resultant, untreated, PTSD.

Those, however, are just just the scandals and headlines. What, you

may ask, of the writing? What about the book many consider to be the

greatest American novel of the post-war era? Or the dozen New Yorker

stories that have influenced scores of beloved writers, from Richard

Yates to John Green? Well, below you’ll find a selection of the first

reviews of each of Salinger’s published books, from the all-powerful Catcher to Three Early Stories (the somewhat controversial publication of which, in 2014, probably would have displeased the author).

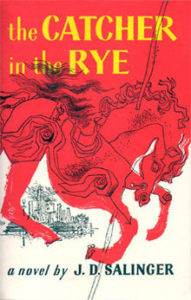

The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

I was surrounded by phonies…They were coming in the goddam window.

“Holden’s story is told in Holden’s own strange, wonderful language by J. D. Salinger in an unusually brilliant novel… Holden

is bewildered, lonely, ludicrous and pitiful. His troubles, his

failings are not of his own making but of a world that is out of joint.

There is nothing wrong with him that a little understanding and

affection, preferably from his parents, couldn’t have set right. Though

confused and unsure of himself, like most 16-year-olds, he is observant

and perceptive and filled with a certain wisdom. His minor delinquencies

seem minor indeed when contrasted with adult delinquencies with which

he is confronted.

Mr. Salinger, whose work has appeared in The New Yorker and

elsewhere, tells a story well, in this case under the special

difficulties of casting it in the form of Holden’s first-person

narrative. This was a perilous undertaking, but one that has been

successfully achieved. Mr. Salinger’s rendering of teen-age speech is

wonderful: the unconscious humor, the repetitions, the slang and

profanity, the emphasis, all are just right. Holden’s mercurial changes

of mood, his stubborn refusal to admit his own sensitiveness and

emotions, his cheerful disregard of what is sometimes known as reality

are typically and heart breakingly adolescent.”

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen