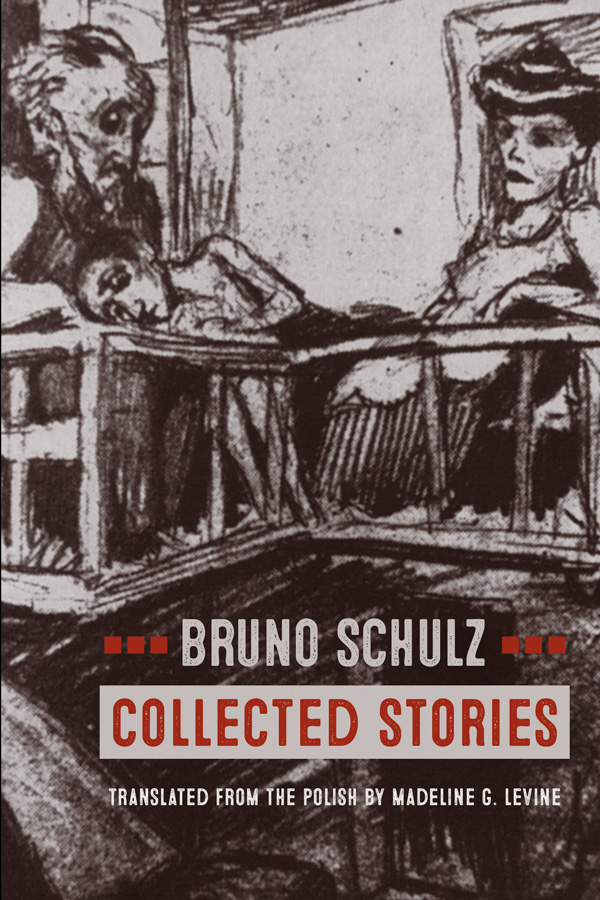

Bruno Schulz (trans. Madeline G. Levine), Collected Stories. Northwestern University Press, 2018. 288 pages.

Twenty-five years before the publication of Derrida’s inquiry into diasporic Jewish poetics and forty-seven years before the release of Kitaj’s diasporist manifesto, Bruno Schulz—a writer of the Jewish diaspora—was murdered by a Gestapo officer while carrying a loaf of bread to his home in Drohobycz, the small Polish town where he spent nearly his entire life. During his lifetime, he published two remarkable books of strange and stirring stories. He left behind another book of four longer stories and the manuscript of an unfinished novel titled The Messiah, entrusted to unknown persons he described only as “Catholics outside the ghetto.” All of this work has been lost.

Schulz’s literary legacy is fractured; absence lies at its heart. In Regions of the Great Heresy (first published in Polish in 1967), a collection of biographical and critical essays on Schulz, Jerzy Ficowski—a Polish poet who, after an early encounter with Schulz’s stories, became an expert on his life and a champion of his work—laments this situation. “Most likely,” he writes, “Schulz’s major work would have been the now lost novel Messiah, in which the myth of the messianic coming was to symbolize a return to the happiness of perfection that existed at the beginning of time.” But the incompletion of Schulz’s oeuvre has not undermined interest in it. Rather, it has fueled it. Philip Roth and Cynthia Ozick, two of the major American Jewish writers of the 20th century, each penned novels that stem from Schulz’s murder and the loss of his work. Roth’s The Prague Orgy (1985) concerns Nathan Zuckerman’s journey to Prague in search of the manuscripts of a murdered writer based on Schulz, while Ozick’s The Messiah of Stockholm (1987)—dedicated to Roth—follows a Swedish man who believes himself to be Schulz’s son and who happens upon what might be the lost manuscript of The Messiah. The tragic truncation of Schulz’s life and the destruction of much of his work have given both his life and his work a diasporic incompletion that has proven aesthetically generative. ... [mehr] https://thenewinquiry.com/the-diasporist-of-drohobycz/

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen