With Couples, Updike served up a whole plate of suet. (Do you understand the genius of Hardwick’s metaphor? Suet is the hard white fat on the loins of beef or mutton.) He worked out the plot in church, jotting down notes on the weekly program—maybe that’s why the book has the air of being so scandalized by itself. It’s the story of twenty alcoholics living in a charming rural outpost called Tarbox, which is starting to get built up. (The nearest abortionist is in Boston.) Their hobbies are drinking gin, frugging, sleeping with each other’s spouses, and gossiping. For members of the Silent Generation, they are very chatty, and make constant efforts to outdo one another in wit. “Welcome to the post-pill paradise” is the book’s most famous line. As Wilfrid Sheed put it in the Sunday Times review, these are “the people who wanted to get away from the staleness of the Old America and the vulgarity of the new,” who wanted “to raise intelligent children in renovated houses in absolutely authentic rural centers.” They are too young to have fought in World War II or believe in God, but too old to join SDS. They will be replaced, at the book’s end, by Boomers who prefer LSD to gin and bitter lemon.

Updike dedicated Couples to his wife, Mary, a decision that his biographer Adam Begley calls “an ironic gesture, certainly, and possibly hostile.” It was no secret that the book was based on the Updikes’ own clique, the horrible-sounding “Junior Jet Set” of Ipswich, Massachusetts. He had so many flings, so close to home, that one female friend found herself wondering, “Am I the only woman in our crowd who hasn’t slept with John?” His editor at Knopf worried about lawsuits, so the New Yorker’s libel lawyer read the manuscript. Updike took out all references to volleyball (his characters instead play basketball), moved Tarbox from the North Shore to the South Shore, and deleted someone’s hair. In a time when novelists write directly about themselves and their friends, these superficial gestures at fictionality are cute, like going to bed in curlers.

I almost forgot—they have names. The principals are Piet and Angela Hanema, Foxy and Ken Whitman, and Freddy and Georgene Thorne. Piet is having an affair with Georgene when the book opens, and begins an affair with Foxy when she moves to town. (Foxy is pregnant with her husband’s child for much of the affair.) In a comic B-plot, the Smiths and the Applebys regularly swap partners and are referred to as the “Applesmiths.” Some people are hard to tell apart, but everyone has “their thing.” Frank Appleby quotes Shakespeare. The Guerins can’t have children. The Saltzes are Jewish. John Ong is a brilliant physicist, and Korean, and no one can understand his accent; the group barely notices when he dies. (His half-Japanese wife is referred to as “the yellow peril.”) You are expecting me to quote some of Updike’s silly sex writing, so fine: “her tranced drained face swims to his and her cold limp lips as he kissed them wear a moony melted stale smell whose vileness she had taken into herself.” Now I’ll quote a sentence that fills me with rage: “Angela and Foxy, their crossed legs glossy, fed into the room that nurturing graciousness of female witnessing without which no act since Adam’s naming of the beasts has been complete.”

Couples earned Updike a million dollars and was on the New York Times fiction best-seller list for thirty-six weeks, six weeks longer than Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge, which probably had nothing to do with Vidal’s statement that Updike “describes to no purpose.” (Couples was number one for one week only, the week of June 30. It interrupted the otherwise uncontested seven-month reign of Arthur Hailey’s Airport, a thriller about the havoc wreaked by a winter storm on an . . . airport.) The book is set in the very recent past, spring 1963 through spring 1964, a period that another novelist would treat with historical irony but that Updike approaches with plausible deniability. We were so much younger then! The novel’s major set piece occurs the night of the Kennedy assassination, at a black-tie dinner dance that the couples do not cancel. They say that people are driven to desire by grief. In this case, Piet is driven to infantilism. He holes up in the bathroom and asks Foxy to nurse him (she’s left the baby at home for a few hours); when his wife knocks on the door, he jumps out the window. Does that sound like satire? The book lays it out like “the warm and fat and glistening ham” served at the party’s end, but Updike never picks up the knife to carve. He is too charmed by his couples, which is to say, by himself. ... [mehr] https://www.bookforum.com/inprint/025_02/19689

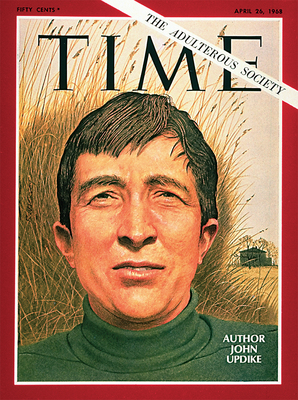

John Updike on the cover of Time, April 26, 1968

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen