On the morning of June 3, 1968, Robert Francis Kennedy, hoping to

secure his late-surging campaign for the Democratic party’s presidential

nomination, was driving in his open-air motorcade through San

Francisco. It was a high, cloud-bright day. Around him the streets were

lined four-people deep. Children ran alongside the car. This was in

Chinatown, one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods.

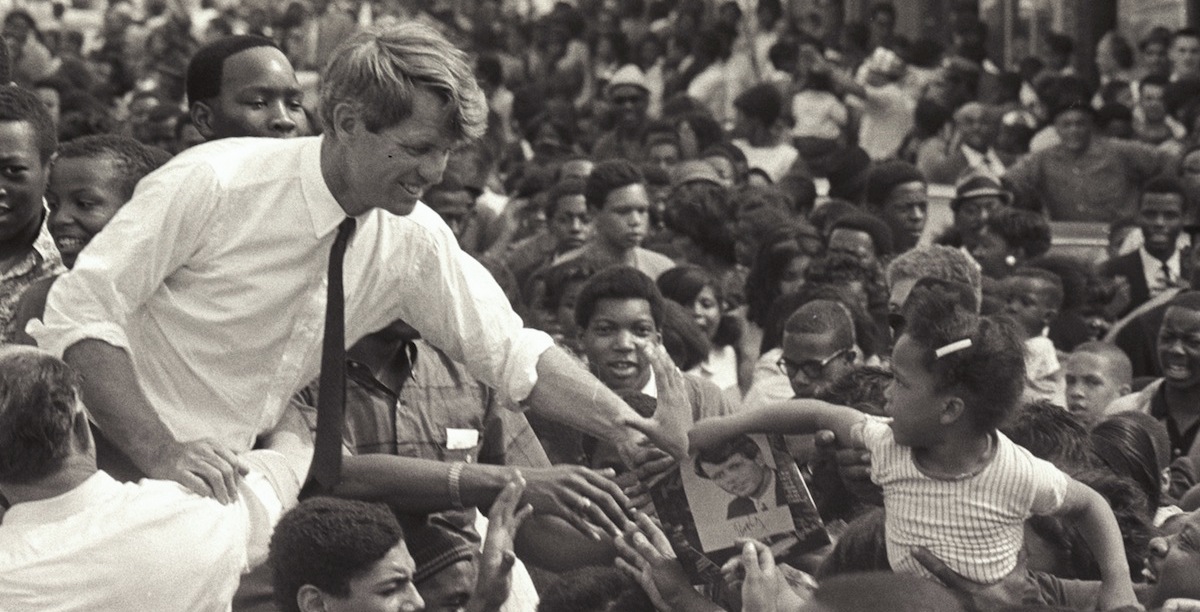

The motorcade was moving slowly. Already they were behind schedule. Kennedy was standing on the convertible’s back bench alongside his wife, Ethel, as they passed the first block, then the second. He kept reaching down to shake hands. In return, the members of the crowd reached up.

It had been like this ever since his campaign first began, 80 days earlier. In his earliest public appearances as a candidate—at the Kansas universities in Lawrence and Manhattan—he’d been overwhelmed by the fervor of the crowds.

Afterward, across his nonstop campaign through the Indiana, Oregon, and California primaries—during which he appealed, first and foremost, to what he liked to refer to as his coalition of the “have nots,” America’s most disadvantaged citizens—people appeared to want, more than anything, to touch him. “They’re here because they care for us,” Kennedy observed, “and want to show us.” On a few occasions he was nearly jerked from the car altogether. The motorcades were monitored by his personal security man, Bill Barry, a former football player at Kent State who, kneeling on the bench of the convertible, would spend hours with his arms wrapped around the waist of the candidate, as to keep him from being carried away.

Early in the campaign, at Kalamazoo’s central square, a young woman surged forward and pulled off Kennedy’s shoe, its laces still tied. At the Greek Theater in Los Angeles so many came out to see him that the resulting traffic jam brought the Griffith Park neighborhood to a halt; eventually people began to abandon their cars on the street. Everywhere he went that spring it was the same: each night his hands would be chafed and bleeding. He made physical contact with more individuals during those few frenetic months than most people do in a lifetime. In May, on the eve of the Indiana primary, his motorcade traveled for nine straight hours from La Porte County to the Illinois border, an endless throng of supporters. For blocks he tossed a basketball back and forth with the same young boy, who had no problem keeping pace. He passed a family that had strapped a mattress to the roof of their parked car, their four children sound asleep on top of it by the time the motorcade appeared. After a while Bill Barry, crouched and clutching the candidate by the waist, lost all sensation in his knees and calves. Near Chicago the frenzy reached a peak, the avenues lined with voters who’d been camped out all day to meet him. The plan had been to go straight to O’Hare Airport. Instead Kennedy ordered the procession forward. “If they’re waiting for me,” he said to Barry, “we’ll go see them.”

“You are the privileged ones here… It’s the poor who carry the major burden of the struggle in Vietnam. You sit here as white medical students, while black people carry the burden of fighting in Vietnam.” He won the May 7 Indiana primary, his first, by a large margin. Over the next four weeks there’d been ups and downs—a resounding victory in Nebraska, as well as a stinging six-point loss in Oregon—but by that bright summer morning in San Francisco, one thing was clear: time was running out.

The all-important California primary would be held the next day, on Tuesday, June 4. To secure his party’s nomination—in an attempt to knock out fellow anti-war Democrat Eugene McCarthy and at the same time fight off the party’s establishment candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a vocal supporter of the administration’s calamitous Vietnam policy—Kennedy needed a convincing win. His slow-moving motorcade through Chinatown marked the start of what was to be an 18-hour, 1,200-mile swing from the Los Angeles basin to the Bay Area and then back again to a fundraiser in San Diego: a final breathless barnstorm to secure the state’s crucial 174 delegates.

Bobby Kennedy was 42 years old. Recently, at the start of 1968—a year that had begun with the Tet Offensive and only gotten worse—he’d decided that he could no longer keep from speaking out against the current administration on the three issues he believed to be ripping America apart: the war in Vietnam, racial injustice, and income inequality. Now, after a furious sprint through the bewildering primary season—at that time, a large number of states refused to hold elections, their delegates controlled, instead, by powerful party bosses like Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley—he found himself in a knock-down fight for the opportunity to become the next president of the United States.

In San Francisco that summer morning, his wife Ethel stood alongside him on the convertible’s bench. She was dusky and sharp-boned, wearing a vermillion coat and white gloves, her shoulders thrown back, a lei of fresh flowers draping her neck. In two weeks they planned to celebrate their 18th wedding anniversary. Already they’d had ten children together. That spring they’d learned she was pregnant with their eleventh.

At the third Chinatown intersection, Kennedy was still shaking hands when a series of deafening shots erupted from the area just ahead of the car.

Ethel threw herself down onto the convertible’s deck. In the crowd people ducked. From alongside the motorcade men in suits reached to shield the candidate and his wife. Eight fierce explosions rattled off in quick succession. It was an instant that lasted no more than a few seconds. The entire time, from his perch on the bench, Robert Kennedy continued to stand. He never moved.

The source of the shots? Fireworks. A long ribbon of them, each one latticed to the next across the open stretch of street the car was now approaching. Perhaps they’d been lit in celebration. Or by children. Regardless: for an instant they had sparked and sounded like the discharge of a gun.

“A tense moment,” the journalist Jules Witcover, who witnessed the event firsthand, would write in 85 Days, his outstanding step-by-step account of the campaign. He was talking about Kennedy’s refusal to duck for cover. “It was as though he had prepared himself for just such a moment, and to endure through it.”

Afterward the gravity of the situation—its sickening resonance—seemed to hit Kennedy. “The candidate looked down to Ethel,” Witcover explained, “then around the car, and motioned to a friend alongside to join her and steady her nerves.”

Together they continued through Chinatown, toward Fisherman’s Wharf, for a private event at Joe DiMaggio’s restaurant. But the sound of the fireworks lingered. That afternoon they flew to Long Beach, motorcaded through Watts and Venice, and then hopped another flight to San Diego. “I don’t feel good,” Kennedy admitted, a rarity for him. ... [mehr] https://lithub.com/the-last-days-of-robert-f-kennedy/

The motorcade was moving slowly. Already they were behind schedule. Kennedy was standing on the convertible’s back bench alongside his wife, Ethel, as they passed the first block, then the second. He kept reaching down to shake hands. In return, the members of the crowd reached up.

It had been like this ever since his campaign first began, 80 days earlier. In his earliest public appearances as a candidate—at the Kansas universities in Lawrence and Manhattan—he’d been overwhelmed by the fervor of the crowds.

Afterward, across his nonstop campaign through the Indiana, Oregon, and California primaries—during which he appealed, first and foremost, to what he liked to refer to as his coalition of the “have nots,” America’s most disadvantaged citizens—people appeared to want, more than anything, to touch him. “They’re here because they care for us,” Kennedy observed, “and want to show us.” On a few occasions he was nearly jerked from the car altogether. The motorcades were monitored by his personal security man, Bill Barry, a former football player at Kent State who, kneeling on the bench of the convertible, would spend hours with his arms wrapped around the waist of the candidate, as to keep him from being carried away.

Early in the campaign, at Kalamazoo’s central square, a young woman surged forward and pulled off Kennedy’s shoe, its laces still tied. At the Greek Theater in Los Angeles so many came out to see him that the resulting traffic jam brought the Griffith Park neighborhood to a halt; eventually people began to abandon their cars on the street. Everywhere he went that spring it was the same: each night his hands would be chafed and bleeding. He made physical contact with more individuals during those few frenetic months than most people do in a lifetime. In May, on the eve of the Indiana primary, his motorcade traveled for nine straight hours from La Porte County to the Illinois border, an endless throng of supporters. For blocks he tossed a basketball back and forth with the same young boy, who had no problem keeping pace. He passed a family that had strapped a mattress to the roof of their parked car, their four children sound asleep on top of it by the time the motorcade appeared. After a while Bill Barry, crouched and clutching the candidate by the waist, lost all sensation in his knees and calves. Near Chicago the frenzy reached a peak, the avenues lined with voters who’d been camped out all day to meet him. The plan had been to go straight to O’Hare Airport. Instead Kennedy ordered the procession forward. “If they’re waiting for me,” he said to Barry, “we’ll go see them.”

“You are the privileged ones here… It’s the poor who carry the major burden of the struggle in Vietnam. You sit here as white medical students, while black people carry the burden of fighting in Vietnam.” He won the May 7 Indiana primary, his first, by a large margin. Over the next four weeks there’d been ups and downs—a resounding victory in Nebraska, as well as a stinging six-point loss in Oregon—but by that bright summer morning in San Francisco, one thing was clear: time was running out.

The all-important California primary would be held the next day, on Tuesday, June 4. To secure his party’s nomination—in an attempt to knock out fellow anti-war Democrat Eugene McCarthy and at the same time fight off the party’s establishment candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a vocal supporter of the administration’s calamitous Vietnam policy—Kennedy needed a convincing win. His slow-moving motorcade through Chinatown marked the start of what was to be an 18-hour, 1,200-mile swing from the Los Angeles basin to the Bay Area and then back again to a fundraiser in San Diego: a final breathless barnstorm to secure the state’s crucial 174 delegates.

Bobby Kennedy was 42 years old. Recently, at the start of 1968—a year that had begun with the Tet Offensive and only gotten worse—he’d decided that he could no longer keep from speaking out against the current administration on the three issues he believed to be ripping America apart: the war in Vietnam, racial injustice, and income inequality. Now, after a furious sprint through the bewildering primary season—at that time, a large number of states refused to hold elections, their delegates controlled, instead, by powerful party bosses like Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley—he found himself in a knock-down fight for the opportunity to become the next president of the United States.

In San Francisco that summer morning, his wife Ethel stood alongside him on the convertible’s bench. She was dusky and sharp-boned, wearing a vermillion coat and white gloves, her shoulders thrown back, a lei of fresh flowers draping her neck. In two weeks they planned to celebrate their 18th wedding anniversary. Already they’d had ten children together. That spring they’d learned she was pregnant with their eleventh.

At the third Chinatown intersection, Kennedy was still shaking hands when a series of deafening shots erupted from the area just ahead of the car.

Ethel threw herself down onto the convertible’s deck. In the crowd people ducked. From alongside the motorcade men in suits reached to shield the candidate and his wife. Eight fierce explosions rattled off in quick succession. It was an instant that lasted no more than a few seconds. The entire time, from his perch on the bench, Robert Kennedy continued to stand. He never moved.

The source of the shots? Fireworks. A long ribbon of them, each one latticed to the next across the open stretch of street the car was now approaching. Perhaps they’d been lit in celebration. Or by children. Regardless: for an instant they had sparked and sounded like the discharge of a gun.

“A tense moment,” the journalist Jules Witcover, who witnessed the event firsthand, would write in 85 Days, his outstanding step-by-step account of the campaign. He was talking about Kennedy’s refusal to duck for cover. “It was as though he had prepared himself for just such a moment, and to endure through it.”

Afterward the gravity of the situation—its sickening resonance—seemed to hit Kennedy. “The candidate looked down to Ethel,” Witcover explained, “then around the car, and motioned to a friend alongside to join her and steady her nerves.”

Together they continued through Chinatown, toward Fisherman’s Wharf, for a private event at Joe DiMaggio’s restaurant. But the sound of the fireworks lingered. That afternoon they flew to Long Beach, motorcaded through Watts and Venice, and then hopped another flight to San Diego. “I don’t feel good,” Kennedy admitted, a rarity for him. ... [mehr] https://lithub.com/the-last-days-of-robert-f-kennedy/

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen