-Patricia Highsmith, diary entry, 1947

Patricia Highsmith wore many hats over the course of her life and

five decade writing career. In many respects, she was a deeply

contradictory figure: a master practitioner of the bleak psychological

thriller who also penned the first, and for several years only,

major lesbian novel with a happy ending; a self-described liberal and

social democrat who seemed to have no qualms about making racist and

antisemitic statements; someone who hated being around people, yet

enjoyed countless affairs and short-lived romances.Though Highsmith’s literary immortality largely rests on her creation of Tom Ripley—the suave, cold-blooded, and utterly amoral protagonist of The Talented Mr. Ripley and its four sequels—both Strangers on a Train and Carol are also rightly considered classics. Notably, the reputations of the “Ripliad,” Strangers, and Carol have all benefited from their acclaimed, and Oscar-nominated, film adaptations.

Below, we take a look at a selection of reviews, both classic and contemporary, of these, Highsmith’s most famous novels, as well as her deliciously-titled 1975 short story collection, Little Tales of Misogyny.

*

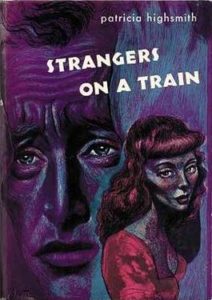

Strangers on a Train (1950)

The night was a time for bestial affinities, for drawing closer to oneself.

…

“Highsmith perverts the workings of sympathy in her suspense stories. Sympathy means imagining oneself in another’s place, but Highsmith makes it difficult for the reader to sympathize with the characters, or for the characters to sympathize with each other. Bruno feels connected to one person only by murdering another, and Guy’s descent offers no relief for a reader looking for someone to root for.

…

“The shared decline of Bruno and Guy is less a morality play than an ugly spectacle of disintegration. ‘I find the public passion for justice quite boring and artificial,’ Highsmith wrote, ‘for neither life nor nature cares whether justice is ever done or not.’ Instead of illustrating a moral, Strangers on a Train throbs with a pervasive and inexorable tension, a gnawing pressure that erodes the characters from the inside.

That tension is Highsmith’s creative signature. Strangers was her debut novel, but her sense of anxious foreboding was already fully formed in the crucible of Cold War paranoia that surrounded her. For Highsmith, who was gay, that paranoia was shot through with anxiety, for American Cold War politics intertwined with an intense homophobia that branded homosexuals as an official national security risk. Highsmith’s creative goal, she wrote in her notebook at the time, was ‘Consciousness alone, consciousness in my particular era, 1950.’

She expressed that consciousness through guilt, but of an unusual sort. Beginning with the character of Guy in Strangers on a Train and continuing through 18 novels and scores of short stories, Highsmith’s inverted version of guilt creates the crime, not the other way around.”

–Leonard Cassuto, The Wall Street Journal, November 22, 2008 ... [mehr] https://bookmarks.reviews/patricia-highsmiths-malcontents-misogynists-and-murderers/

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen