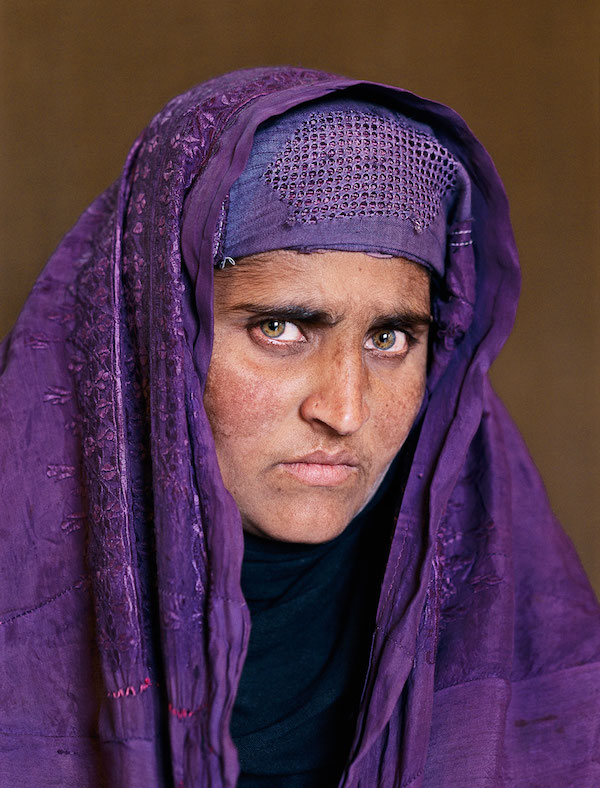

One of these pictures, of Sharbat Gula, the green-eyed Afghan teenager he shot in a refugee camp in 1984, has been called one of the most widely recognized photographic images ever. Being Steve, he tracked the woman down 17 years later and photographed her again.

He was a traveler before he was a photographer, and he has always been a risk-taker. As a 22-year-old looking for subjects, he hitchhiked from his home in the US and traveled through Mexico and Central America, as far as Panama. Before he was 30 he had traveled through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, and alone down the Nile, into Uganda and Kenya; he lived a vagabond life in India for two years in the late 1970s, and visited Nepal and Thailand. And he sneaked into Afghanistan, disguised as an Afghan peasant. He was still in his twenties.

Famously, early in 1979, during a period of civil war, he grew a beard, dressed in native garb, a shalwar kameez, and followed a group of five Afghans from Chitral in the rugged Northwest Frontier Province in Pakistan to the Kunar Valley in Afghanistan, photographing burned-out villages and bombings and atrocities. He walked the whole way, on mountain paths, living on berries, sleeping in huts. Ten months later, when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, his were the first photographs to be published in Europe and America, of defiant Afghan mujahideen.

After another visit to Afghanistan and assignments in Beirut, Balochistan, and the Cambodian border, he acquired the reputation as a war photographer. “But that wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted to be a freelance, going wherever I wanted to go.”

He got his wish—in his travels in Asia, Latin America, Africa, and Europe, he has dedicated himself to his art, looking for the light. Many of his pictures are historic, and he has incidentally chronicled in his photographs the habits and routines and costumes of a vanished world.

–Paul Theroux, essayist, novelist, and travel writer

| |||

| Sharbat Gula, Afghan Girl. Peshawar, Pakistan, 1984. Copyright: Steve McCurry |

Reunited

Many people know that Steve was able to find Sharbat Gula, the young Afghan girl with the piercing green eyes whose iconic 1984 portrait is synonymous with his work. By the time Steve tracked her down in Afghanistan, in 2002, after several unsuccessful attempts in the 1990s, Sharbat was in her thirties and a mother to children of her own. The youthful beauty that Steve had captured all those years earlier in Pakistan was forever memorialized in his photograph and in the world’s imagination, but Sharbat Gula continued her life in the real and very harsh world without any knowledge of her celebrity. She had returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan in 1992, and had endured nearly a decade of life under the Taliban.

When Steve and the National Geographic’s documentary filmmakers finally found her, they were the first to show her the famous portrait. Steve was able to make another portrait of Sharbat Gula, after her husband gave permission, although at first she refused to meet with him because she worried about violating religious and cultural norms. In the new portrait, her intense gaze is unmistakable, but her face shows the worry and stress of the nearly two decades between the two portraits. Though still a young woman, she appears weathered and haunted. Comparing the portraits side by side, we are confronted with the difficulty of life in a region of perpetual conflict, poverty, lack of sanitation and clean water, and food shortages.

Sharbat Gula, Peshawar, Pakistan, 2002. Copyright Steve McCurry.

In April 2002, National Geographic published a cover with Sharbat Gula in a purple burka, her face totally obscured, holding a print of Steve’s original portrait, with the title, “Found.” Steve’s attempts to find her and make a portrait of her as an adult also formed part of the documentary, and made headlines around the world, which may have led some to conclude that tracking down a former portrait subject was a novel idea. It was anything but. The reality is that Steve revisits specific places, and the people he photographed in them, as a matter of habit—and it’s a habit as old as his first European sojourn in the late 1960s.

On a trip in 1969, Steve befriended a student about his same age named Tomas Södergren while riding a train through Sweden. Tomas invited Steve to come stay at his family home in Stockholm, and Steve accepted. He made some lovely portraits of Tomas on a roof with the skyline of Stockholm in the background, and Tomas—also a photographer—made similar portraits of Steve. But what they really made was an enduring friendship, which persists almost a half century later.

I’ve always felt happy for Steve that even with his extraordinarily peripatetic lifestyle, wherever he is, he never seems to be without friends. When it comes to the subjects of his photography, however, reuniting with old haunts and faces from the past also serves a critical artistic and documentary function. In a tiny fraction of a second, the shutter button freezes people and places in time—but as we see so clearly, life goes on, sometimes in dramatic fashion.

Ahmadi Oil Fields, Kuwait, 08/1991. Environmentalists Rick Thorpe and

Michael Bailey of Earthtrust examine a field where the ground has been

encrusted with oil. Copyright Steve McCurry.

Ahmadi Oil Fields, Kuwait, 08/1991. Environmentalists Rick Thorpe and

Michael Bailey of Earthtrust examine a field where the ground has been

encrusted with oil. Copyright Steve McCurry. Sahel, Mali. 1986. A boy rides a donkey. Copyright Steve McCurry.

Sahel, Mali. 1986. A boy rides a donkey. Copyright Steve McCurry. Moscow, Rybinsk, Russia, 03/2015. Woman in street walking beneath airplane. Copyright Steve McCurry.

Moscow, Rybinsk, Russia, 03/2015. Woman in street walking beneath airplane. Copyright Steve McCurry.

Village Boy. Kamdesh, Nuristan, Afghanistan, 1992. Copyright Steve McCurry.

From Steve McCurry: A Life in Pictures: 40 Years of Photography by Bonnie McCurry and Steve McCurry. Copyright © 2018 by Bonnie McCurry and Steve McCurry. Excerpted by permission of Laurence King Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

via https://lithub.com/paul-theroux-on-the-iconic-photographs-of-steve-mccurry/

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen