The story

Vita Sackville-West wrote for the library of Queen Mary’s Dollhouse is a

jeu d’esprit. Vita was not a humorist, nor was she much given to

whimsy, but her teasing children’s tale of a boastful, “lively . . .

inquisitive spirit,” whose “dark little clubbed head,” like Vita’s,

“gave her a boyish, page-like appearance,” is essentially a joke. As

such it is unique among Vita’s fiction.

First conceived in 1921, Queen Mary’s

Dollhouse was the brainchild of Princess Marie Louise of

Schleswig-Holstein, a first cousin of the Queen’s husband, George V.

Vita’s inclusion among the 171 authors to whom the Princess wrote

requesting a special contribution for the dollhouse library is proof of

the stature she had attained early in her career. By 1923, aged 31, Vita

had published in the space of six years three novels, a novella, two

volumes of poetry, and two nonfiction titles based on her family

history: Knole and the Sackvilles and The Diary of Lady Anne Clifford.

Her recent election to the committee of the PEN Club further stamped

her as an established author. The Princess’s intention was to gather “a

representative, rather than a complete” kaleidoscope of the period’s

leading writers. Healthy sales figures and a degree of critical acclaim

directed her to Vita. In this rarefied prewar world, Vita’s status as

the only daughter of Lord Sackville of Knole was an added

recommendation. The invitation was flattering. It placed Vita on a par

with established best-sellers Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, and

Rudyard Kipling and, more remarkably, Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad, and

the poet laureate, Robert Bridges.

–Matthew Dennison

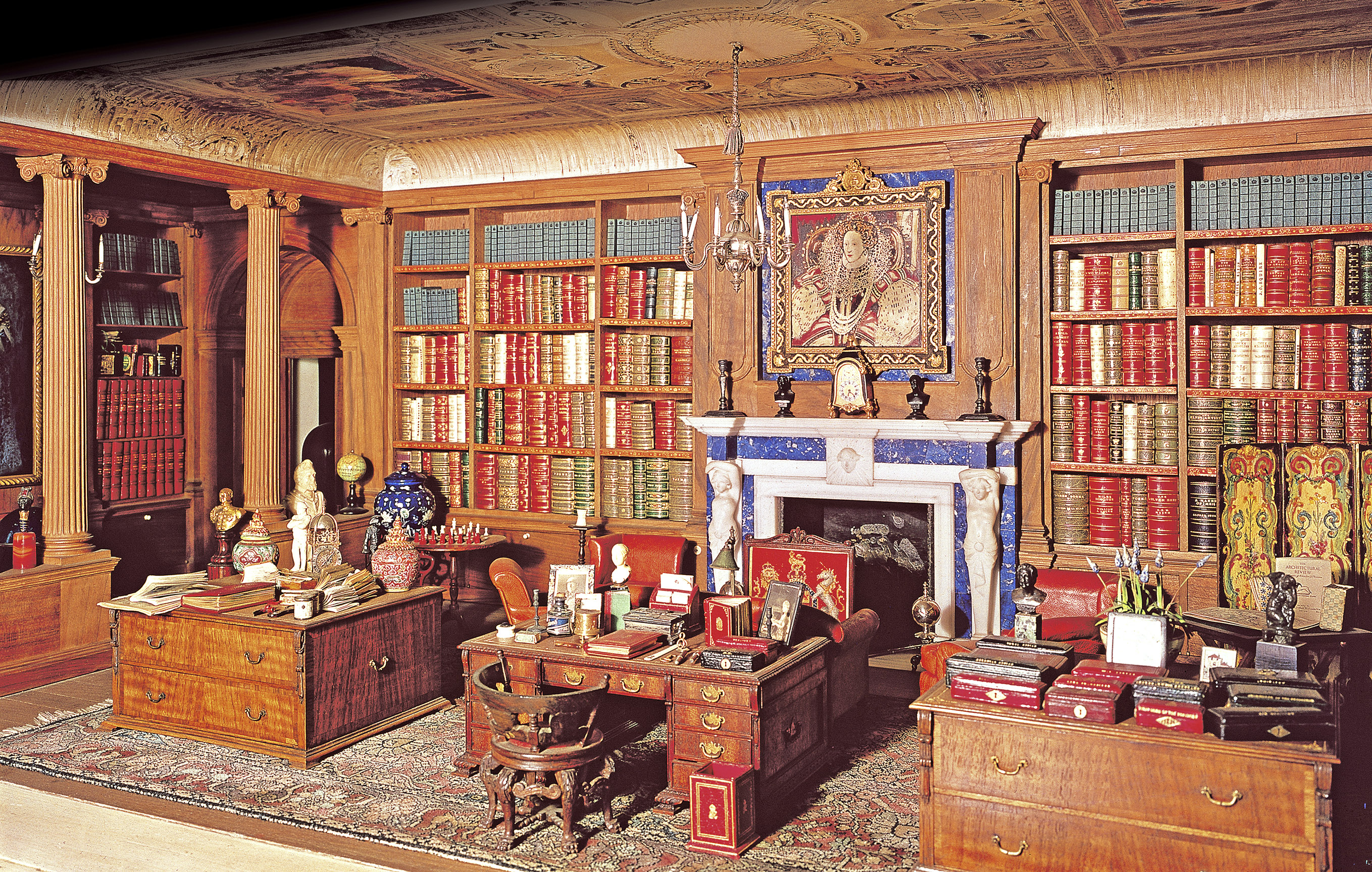

Queen Mary’s Dollhouse library

Queen Mary’s Dollhouse library

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen